William Howard Russell

William Howard Russell | |

|---|---|

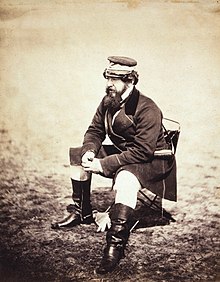

William Howard Russell, ca. 1854 | |

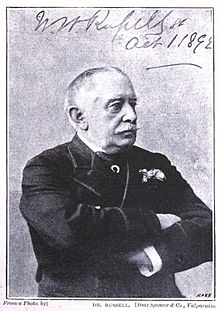

| Born | 28 March 1827 Tallaght, County Dublin, Ireland |

| Died | 10 February 1907 (aged 79) London, England |

| Occupation | Reporter, writer |

| Genre | Journalism |

| Spouse | Mary Burrows (died 1867) Countess Antoinette Malvezzi |

| Children | 4 |

Sir William Howard Russell, CVO (28 March 1827 – 10 February 1907) was an Irish reporter with The Times, and is considered to have been one of the first modern war correspondents. He spent 22 months covering the Crimean War, including the Siege of Sevastopol and the Charge of the Light Brigade. He later covered events during the Indian Rebellion of 1857, the American Civil War, the Austro-Prussian War, and the Franco-Prussian War. His dispatches from Crimea to The Times are regarded as the world's first war correspondence.[1]

Career

[edit]As a young reporter, Russell reported on a brief military conflict between Prussian and Danish troops in Denmark in 1850.

Initially sent by the editor John Delane to Malta to cover British support for the Ottoman Empire against Russia in 1854, Russell despised the term "war correspondent" but his coverage of the conflict brought him international renown, and Florence Nightingale later credited her entry into wartime nursing to his reports. The Crimean medical care, shelter and protection of all ranks by Mary Seacole[2] was also publicised by Russell and by other contemporary journalists, rescuing her from bankruptcy.

Russell was described by one of the soldiers on the frontlines thus: "a vulgar low Irishman, [who] sings a good song, drinks anyone's brandy and water and smokes as many cigars as a Jolly Good Fellow. He is just the sort of chap to get information, particularly out of youngsters."[3] This reputation led to Russell's being blacklisted from some circles, including British commander Lord Raglan, who advised his officers to refuse to speak with the reporter.

His dispatches were hugely significant; for the first time the public could read about the reality of warfare. Shocked and outraged, the public's backlash from his reports led the Government to re-evaluate the treatment of troops and led to Florence Nightingale's involvement in revolutionising battlefield treatment.

On 20 September 1854, Russell covered the battle above the Alma River—writing his missive the following day in an account book seized from a Russian corpse. The story, written in the form of a letter to Delane, was supportive of the British troops and paid particular attention to the battlefield surgeons' "humane barbarity" and the lack of ambulance care for wounded troops. He later covered the Siege of Sevastopol where he coined the phrase "thin red line" in referring to British troops (93rd Highlanders) at Balaclava, writing that "[The Russians] dash on towards that thin red streak topped with a line of steel...".

Following Russell's reports of the appalling conditions suffered by the Allied troops conducting the siege, including an outbreak of cholera, Samuel Morton Peto and his partners built the Grand Crimean Central Railway, which was a major factor leading to the success of the siege.[4]

Russell wrote about his meetings with Mary Seacole and wrote highly of Seacole's skill as a healer: "A more tender or skilful hand about a wound or a broken limb could not be found among our best surgeons."[5]

He spent December 1854 in Constantinople on holiday, returning in early 1855. Russell left Crimea in December 1855 to be replaced by the Constantinople correspondent of The Times.

In 1856, Russell was sent to Moscow to describe the coronation of Tsar Alexander II and in the following year was sent to India where he witnessed the final re-capture of Lucknow (1858).[6]

In 1861 Russell went to Washington and returned to England in 1863. In July 1865 he sailed on the Great Eastern to document the laying of the Atlantic Cable and wrote a book about the voyage[7] with colour illustrations by Robert Dudley.[8] He published diaries of his time in India, the American Civil War[9] and the Franco-Prussian War, where he describes the warm welcome given him by English-speaking Prussian generals such as Leonhard Graf von Blumenthal.

Russell later accused fellow war correspondent Nicholas Woods of the Morning Herald of lying in his articles about the war[clarification needed] to try to improve his stories.

Later life

[edit]

In the 1868 General Election, Russell ran unsuccessfully as a Conservative candidate for the borough of Chelsea.

He retired as a battlefield correspondent in 1882 and founded the Army and Navy Gazette.

Russell was knighted in May 1895. He was appointed a Commander of the Royal Victorian Order (CVO) by King Edward VII on 11 August 1902,[10][11] a dynastic order handed out by the King without government interference. During the investiture, the King reportedly told Russell 'Don't kneel Billy, just stoop'.[3]

Russell died in 1907 and is buried in Brompton Cemetery, London.

Personal life

[edit]

Russell was born into a middle-class family with a mixed Protestant and Catholic background—his father was Protestant, and his mother Catholic. He was baptized into the Church of Ireland but attend Catholic mass and was tutored in religion by his Catholic grandmother.[12] Growing up, his family faced significant financial difficulties, which led to frequent moves between Dublin and Liverpool. Despite this, Russell was able to pass the entrance exams for Trinity College in 1838, though he never completed a degree.[13]

He married twice. His first marriage was to Mary Burrows, of Irish Catholic origin. Despite the hostility of her family, they married on 16 September 1846 in an Anglican ceremony in Howth and had 4 children. She died in 1867.[12] Russell remained widowed for several years before remarrying to 36 year old Countess Antoinette Malvezzi from Ferrara, an Italian noblewoman, in February 1884. The marriage was again met with controversy, as the bride's family insisted that any children from the union be raised Roman Catholic, a demand that Russell refused. The marriage was held in Paris in three ceremonies, one Catholic at the Paroisse Saint-Honoré d'Eylau, another Anglican at the British Embassy, and a third in a civil ceremony. They remained married until Russell's death in 1907.[14][15] They had two sons and one daughter, none of whom had offspring.

Russell was a Freemason.[14]

As a young man, Russell had had an affair with a German woman from Heligoland, Anna Catharina Oelrichs, with whom he had a son, William Russell, in 1863.[16] There are still Russells on Heligoland.

Legacy

[edit]Russell's dispatches via telegraph from the Crimea remain as his legacy; for the first time he brought the realities of war home to readers. This helped diminish the distance between the home front and remote battle fields. They were collected, edited by the author, and published in two volumes as The War in 1856, revised and retitled History of the British Expedition to the Crimea in 1858.

Russell's war reporting (often in semi-verbatim form) features prominently in Northern Irish poet Ciaran Carson's reconstruction of the Crimean War in Breaking News (2003).

His biography was written by the first special correspondent of the Manchester Guardian[17] John Black Atkins.[18]

There is a bust of Russell in the crypt at St Paul's Cathedral.[19]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Smith, Hannah (19 June 2019). "Graves of Britain's Crimean War Dead Are Desecrated, Exploited and Forgotten". Pulitzer Center. The Times. Retrieved 1 April 2023.

Meanwhile, the journalist William Howard Russell sent dispatches back from Crimea to this newspaper, which are recognised as the world's first war correspondence. It was Russell's detailed account of the Charge of the Light Brigade, the British cavalry's doomed advance on Russian positions, that inspired Tennyson's eponymous poem.

- ^ Palmer, A (May 2006) [Sept 2004]. "Seacole, Mary Jane (1805–1881)". Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/41194. Retrieved 18 August 2010. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.).

- ^ a b Sweeney, Michael S (2002), From the Front: The Story of War, National Geographic Society.

- ^ Cooke, Brian (1990). The Grand Crimean Central Railway. Knutsford: Cavalier House. pp. 14, 18, 143–49. ISBN 0-9515889-0-7.

- ^ "Mary Seacole by Jane Robinson". The Independent. London. 21 January 2005. Retrieved 24 February 2023.

- ^ Ferdinand Mount, "Atrocity upon atrocity",Times Literary Supplement, 23 February 2018, page 14.

- ^ "Russel", The Atlantic Telegraph, Atlantic cable.

- ^ Robert Dudley biography, Atlantic cable.

- ^ Russell, William Howard (1863). My diary North and South. Boston: T.O.H.P. Burnham.

- ^ "Court Circular". The Times. No. 36844. London. 12 August 1902. p. 8.

- ^ "No. 27467". The London Gazette. 22 August 1902. p. 5461.

- ^ a b Atkins, John Black (1911). The life of Sir William Howard Russell, The First Special Correspondent. London: John Murray. p. 6, 60.

- ^ Hastings, Max (1995). William Russell Special Correspondent of the Times. London: Folio Society. p. 11.

- ^ a b Hankinson, Alan (1982). Man of wars, William Howard Russell of The Times. London: Heinemann. p. 256-257. ISBN 978-0-435-32395-0.

- ^ Martin, Crawford (1992). William Howard Russell's Civil War: Private Diary and Letters, 1861-1862. Athens: University of Georgia Press. p. 46. ISBN 978-0-8203-1369-6.

- ^ ENK (28 November 2010). "Lord William Howard Russell". Helgoland-Genealogie (in German). Retrieved 18 July 2019.

- ^ Roth, Mitchel P (1 January 1997). Historical Dictionary of War Journalism. Greenwood. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-313-29171-5.

- ^ Perry, James M. "The World's Greatest War Correspondent". Book review. The New York Times. Retrieved 28 October 2013.

- ^ "Memorials of St Paul's Cathedral" Sinclair, W. p. 465: London; Chapman & Hall, Ltd; 1909.

External links

[edit] Works by or about William Howard Russell at Wikisource

Works by or about William Howard Russell at Wikisource- Works by William Howard Russell at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about William Howard Russell at the Internet Archive

- Works by William Howard Russell at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- 1827 births

- 1907 deaths

- British people of the Crimean War

- Burials at Brompton Cemetery

- Commanders of the Royal Victorian Order

- 19th-century Irish journalists

- Irish knights

- Irish war correspondents

- Knights Bachelor

- Writers from County Dublin

- The Times people

- People of the American Civil War

- People of the Franco-Prussian War

- People of the Austro-Prussian War

- Irish Anglicans

- Irish Freemasons

- People associated with Trinity College Dublin